Wayside Crosses

par Joly, Diane

Nearly3,000 wayside crosses are still standing along the highways and byways of theProvince of Quebec. They representa precious heritage-a legacy of the past. The first crosses were erected by Jacques Cartier as a symbol ofterritorial appropriation. Later,the pioneers used them to mark the founding of a village and French Canadianpeasant farmers (then known as habitants) did thesame upon staking their land claims. All sorts of reasons have led French Canadians to put up waysidecrosses: farmers set them up closeto their fields for divine protection; parish priests erected them to indicatethe site of a future church; parishioners raised them up on the halfway pointalong a concession or range road, where they would gather for the eveningprayer. Although wayside crossesare first and foremost religious objects, over time they have taken on a moreheritage-oriented significance, their distinctive outline characterising aparticularity of the Quebec countryside that has come to be associated with thefaith of the French Canadian forefathers.

Article disponible en français : Croix de chemin

The Origins of the Wayside Cross

Thewayside cross probably originated with the Celtics in Lower Brittany, Ireland,Scotland, and Wales. The firstcrosses were likely erected during the High Middle Ages by Christian monks fromthose lands.

In 1534,Jacques Cartier raised the first crosses in Canada to affirm his claim toterritory in the name of the King of France. Later, explorers and missionaries followed suit to marktheir passage through new territories. The custom was subsequently passed on to the first settlers who erectedcrosses upon opening new roads or staking land claims. The presence of crosses in thecountryside was noted in travel accounts as early as 1749. In 1776, Thomas Anburey wrote that

[t]hese crosses, however good theintention of erecting them may be, are continually the causes of great delaysin travelling, which to persons not quite so superstitiously disposed as theCanadians, are exceedingly unpleasant in cold weather; for whenever the driversof the calashes, which are open, andnearly similar to your one horse chaises,come to one of them, they alight, either from their horses or carriage, fall ontheir knees, and repeat a long prayer, let the weather be ever so severe.(NOTE 1)

Over theyears, wayside crosses were often featured in tourist guides. Apparent religious devotion wassometimes actually staged for the benefit of onlookers. For example, at the turn of the 20thcentury, William Parker Greenough expressed great indignation over the factthat French Canadians would offer to pretend to pray before their waysidecrosses while he took a picture.(NOTE 2)

TheVarious Types of Wayside Crosses and their Functions

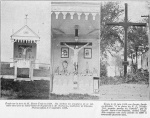

There arethree types of wayside crosses. The simple cross is unadorned or has a few decorative elements at theends or at the centre point of the cross. This variety is found especially on the Gaspé Peninsula, in the regionof Côte-Nord and in Charlevoix, and more than twenty such crosses also dot theAcadian countryside. A secondtype, the cross featuring instruments of the Passion, bears symbolic objectslinked to the Passion of Christ: lance, sponge, nails, hammer, whip, crown of thorns, and/orrooster. More often than not,these crosses are found in the farming regions around Montreal, in the EasternTownships (Estrie) and in southern Quebec. The last category of cross is the roadside crucifixionscene, or Calvary monument, that includes a sculpted Christ, sometimesaccompanied by those who witnessed his death. Many Calvaries are covered by ashelter. They can be seen all overQuebec, with the oldest located along the St. Lawrence River. Twenty or so crosses of all three typescan also be found near St. Boniface, Manitoba.

The roleof the wayside crosses has changed over time. The first crosses served to assert the French claim to theterritory. Later, parish priestsstarted erecting them to delineate the boundaries of a parish or indicate the siteof a future church. Other crossescommemorated a person or an important event. Crosses were also raised in order to obtain a favour or as asign of gratitude for a favour obtained. Finally, crosses were set up very close to cultivated fields as anappeal for divine protection against the natural scourges that afflictharvests: drought, insectinfestations, etc.

AnEmerging Heritage Concept

Around theturn of the 20th century, educated French Canadians started to becomeinterested in wayside crosses. Writing in the Bulletin des Recherches Historiques, a historicaljournal, in 1896, a reader asked exactly where Jacques Cartier's cross waserected in the Gaspé. Subsequently, other readers of the Bulletin were curious to knowthe names of those who built and raised the crosses and why they were actuallyerected.

In 1916,following a literary contest organized by the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montréal [Montreal Society of SaintJohn the Baptist], a collection of texts about wayside crosses waspublished. In the preface and the introductionof the resulting volume of texts, the dual perception of society concerning ofthe nature of these crosses is revealed. While the author of the preface asserted that the crosses have both areligious and a patriotic function, the author of the introduction, who was alsothe contest's organiser, offered an aesthetic assessment concerning the formalaspect of crosses. He was particularly interested in the customs related to thecrosses, all the while recognizing their religious function. The competition judges sided with the organizer,since the majority of the texts selected for the collection dealt with theiconography and customs linked to the crosses. This continued perception of the utilitarian function of thewayside crosses, coupled with an added aesthetic perspective, marked thebeginning of their recognition as a heritage asset, a trend that reached itspeak in the 1960s when a first wayside cross was classified as a historicalmonument.

TheContribution of Édouard-Zotique Massicotte

Spurredon by Édouard-Zotique Massicotte(NOTE 3), intense collection and distribution of informationconcerning wayside crosses was undertaken during the 1922-25 period. Equippedwith a questionnaire sent to local officials, notaries and parish priests, in1922, Massicotte began to put together a photographic inventory and to documentthe crosses. He also met with theowners of private crosses.(NOTE 4) Thepreliminary results of his survey, accompanied by 27 photographs of crosses,were published in the second edition of La Croix du Chemin [The Wayside Cross] (1923), in whichMassicotte includes a foreword calling upon civil authorities to protect thewayside crosses. Next, hepublished seven articles in the Bulletindes Recherches Historiques [Historical Research Bulletin], in which heprovides a review of existing literature on the matter. He also describesseveral crosses in the articles, giving an account of their histories. Thefollowing year, in Montreal, the SociétéSaint-Jean-Baptiste erected the Mount Royal Cross. The 1925 edition of the Almanach du Peuple[People's Almanach] featured a number of wayside crosses and published theresults of Massicotte's survey. InJune of that same year, an allegorical float representing a wayside cross wasincluded in Montreal's Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day parade, which was organized byMassicotte. In the souvenir albumcommemorating the parade, Massicotte asserts that such monuments weredefinitely heritage calibre cultural items.

AnAmbiguous Perception of the Heritage Value of Wayside Crosses

Althoughthe elite (particularly of Montreal) perceived wayside crosses to be heritageassets, for most of society, it has remained an essentially religiousobject. In Montreal, waysidecrosses have on several occasions been integrated into processions and remembranceevents in the context of Quebec's national holiday. For example, in 1932 they were presented as an ancestralheritage legacy around which people would gather for the evening prayer. In 1939, their origins in Brittany werehighlighted. In 1950, they were consideredto be a reflection of ancient customs, and in 1952, they were recognized forbearing witness to the deep faith of the rural population, as well as for therichness of their iconography and the customs associated with them. In 1954, one of Massicotte's friends,Léon Trépanier, published a series of articles on wayside crosses in thejournal La Patrie, in which he presented them as objects having both a religiousand heritage-related significance, all the while highlighting their artisticand cultural features.

Otherarticles written between 1930 and 1960 focused strictly on the religiousdimension of wayside crosses. Forinstance, in 1935, during a sermon to mark the raising of a wayside cross, thepresiding priest asserted that this raising "represents the best testimony tothe survival of the faith in French Canada and of the Christian traditionsbequeathed by our forbearers."(NOTE 5) Inanother article, published in 1943, the author congratulated French Canadianpeasants "for having so well protected the precious heritage of faith passed onby their ancestors."(NOTE 6) Inthis context, the perception of the heritage value of wayside crosses remainedfocused on the promotion of an ancestral religious practice deemedexemplary. Throughout the years,this particular heritage-related perspective has endured, and thus, theperception of wayside crosses has gradually been evolving from religiousobjects into cultural artefacts. Such artefacts serve as integral components inthe larger scheme of French Canadian history and identity.

TheEthnological Contribution of Jean Simard

In 1972,art historian and ethnologist Jean Simard(NOTE 7) published an article in which he presented Calvalriesas ancestral heritage objects. Inhis text, which was distributed throughout Quebec, he outlined the history ofthe crosses, provided a literature and iconography review, and proposed apreliminary classification system. Finally, he focused on an exceptional artist, Louis Jobin, known for hismany roadside Calvaires. Simardspoke of the religious history of wayside crosses and their newly foundheritage-related role while describing them as "evidence of a faith-basedpast."(NOTE 8) This article helped put wayside crosses on the mapin three fields of study: art,culture, and religious heritage.

Over theyears, Jean Simard has written a number of texts on the matter. While otherauthors have presented the wayside crosses of their regions in local newspapers,Simard has rather been working closely with two innovative studies: one thatanalyses wayside crosses from the point of view of Quebec art history, whereasanother makes an exhaustive inventory of their formal features.(NOTE 9) From1972 to 1979, with the assistance of Quebec's Ministère des Affaires Culturelles [Ministry of Cultural Affairs]and a dozen or so students, Jean Simard made a complete inventory of thewayside crosses throughout of the Province of Quebec. In the following phase of the project, the results of thissurvey were compared with other data gathered during a wide-scale inventory ofQuebec heritage conducted by the Government of Quebec.

Theresults of the analysis were published in 1995 in a first work that provided anoverview of the state and condition of wayside crosses in Quebec. The study listed 704 crosses selectedfor their characteristic features. The diachronic analysis was carried out over a period of 20 years andrevealed that a number of crosses had indeed disappeared, but that new ones hadbeen erected, either using traditional methods or modern techniques andmaterials. Among the 704 crossesselected, Jean Simard chose 25 and declared them a heritage treasure of thepeople of Quebec, given their exceptional value.

WaysideCrosses Today

Protectingand preserving wayside crosses is no easy task. First of all, this insitu heritage is at the mercy of bad weather and the extreme climate so typicalof Quebec and the rest of Canada. Secondly, the process of institutional protection is difficult toimplement since most crosses are privately owned and thus, an application forheritage status must be submitted for each individual cross. As things currently stand in Quebec, ofthe 3,000 or so wayside crosses that have been indexed, only 53 are protectedby legislation, and 26 classified as historical monuments.(NOTE 10) Finally,changes in ownership and the indifference of some owners, have led to theneglect or dismantling of numerous crosses. On the other hand, if some crosses are now in a pitifulstate, others are still gathering places, particularly during the month of May(which is devoted to Mary). Furthermore, the careful maintenance of manycrosses reveals that-in the eyes of their owners-they are still in some waysacred.

Theheritage value of wayside crosses is now recognized in many regions of Quebec. Historical societies and other localcultural organizations would like to see more conservation activities showcasingthese heritage assets, particularly tours and brochures, heritage competitions,and Web sites. Local lists ofwayside crosses have also been compiled and meetings with owners have beenarranged, so as to record the history of the crosses and begin to create visualarchives. In the regions,partnerships with private owners have been established in order to ensure thattheir crosses are maintained according to recognized conservation standards. Thus, it would appear that future of this"lesser but not the least attractive legacy of our ancestral heritage"(NOTE 11) is quite optimistic. The next step to preserving the heritage status of theseattractive yet fragile objects of folk culture would be the officialrecognition by the Quebec Ministère de laCulture, Communications et de la Condition Féminine [Ministry of Culture,Communication and the Condition of Women] of the need to protect the mostvaluable of the crosses as cultural assets-provided that the municipalitiesconcerned are willing take the trouble to apply for it.

DianeJoly

Art and Heritage Historian

I would like to thank Jean Simard who reviewed and commented upon the initialversion of this article.

NOTES

1. Thomas Anburey, Travels through the interior parts of America, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1923, pp.61-62.

2. William Parker Greenough, CanadianFolk-Life and Folk-Lore, s.l., s.n., 1897, pp. 69-70.

3. Édouard-Zotique Massicotte was alawyer, archivist, journalist, folklorist, playwright, botanist, poet andhistorian. For over 60 years, hecompiled a collection French-Canadian historical accounts, legends, songs,customs, and traditions and drew up a list of cultural objects associated withgroup identity. For morecontextual information concerning his literary works on folklore see LucLacourcière, "E.-Z. Massicotte, son œuvre folklorique," Les archives defolklore, No. 3 (Québec, Fides, 1946), pp. 7-12.

4. Massicotte collaborated with MariusBarbeau (National Museum of Man, Ottawa), in order to develop of hisphotographs, and with the Commission desMonuments Historiques de la Province de Québec [Commission for HistoricMonuments of the Province of Quebec] to cover his travel expenses. Concerning the institutional crosseserected by elect churchmen, orders, and members of the clergy, he sought todiscover the historical reasons for raising them, as well as the variouscustoms associated with such crosses. As for crosses raised by private citizens, his method was to meet withthe owners and record the date on which it was raised, as well as anyhistorical information associated with it.

5. S. A., "La bénédiction d'une croix àCôte-de-Liesse," La Presse, June 17, 1935, p. 23. [Original citation translated intoEnglish]

6. "Les croix de chemin à travers lapatrie canadienne," Le monde rural. Illustré pour famille, 1943, p. 63. [Originalcitation translated into English]

7. From 1972 to 2000, Jean Simard, fullprofessor at Laval University, taught the Ethnology of Quebec and NorthAmerican French Speakers. He wasparticularly interested in folk-art, folk religion, and religious heritagetraditions, on all of which he has published numerous articles and majorwritten works. He is still activelyinvolved in the field. Currently he is serving as administrator of the Société Québécoise d'Éthnologie [QuebecEthnology Society]. He also participates in various conferences and seminarsconcerning heritage matters, whether as an expert consultant or guest speaker,in addition to contributing to specialized studies in the field. His survey on religious heritage, LeQuébec pour terrain. Itinéraire d'un missionnaire du patrimoine religieux [Grassroots Quebec: the Itinerary of aMissionary of Religious Heritage], published in 2004 by the Presses del'Université Laval, outlines his career and his passion for Quebec heritage.

8. Published in 1972, "Perspectives," wasalso included in certain daily newspapers: Voix de l'Est (Granby), Le Soleil (Quebec City),La Tribune (Sherbrooke), Le Nouvelliste (Trois-Rivières andQuebec City) and Le Droit (Ottawa).

9. John R. Porter and Léopold Désy, Calvaireset croix de chemin du Québec, préface de Jean Simard, Montréal: Hurtubise,1973, 145 p. and Paul Carpentier, Les croix de chemin: au-delà du signe, Ottawa, NationalMuseums of Canada, 1981, 484 p. The latter text is the author's doctoral thesissupervised by Jean Simard.

10. According to the index of Quebeccultural heritage on the Web site of the Ministèrede la Culture, des Communications et de la Condition feminine [Ministry ofCulture, Communications and for the Condition of Women] (www.mcc.gouv.qc.ca),consulted in December 2007. Projects for classifying and citing wayside crosses are still in progress.

11. S. A., Processions de laSaint-Jean-Baptiste: en 1924 et1925, Montréal, Librairie Beauchemin, 1926, p. 269. Massicotte is theauthor of this work. [Original citation translated into English]

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Carpentier,Paul, Les croix de chemin : au-delà du signe, Ottawa, Musées nationaux duCanada, 1981, 484 p.

Massicotte,Édouard-Zotique, "Nos croix de chemin", Bulletin des recherches historiques, April 1923, vol. XXIX, no 4, 1923, pp. 125-127; May 1923, vol. XXIX, no 5, 1923,pp. 142-143; August 1923, XXIX, no 8, 1923, pp. 229-231; September 1923, XXIX, no9, 1923, pp. 269-270; September 1923, XXIX, no 11, 1923, pp. 350-352; February1924, XXX, no 2, 1924, p. 55-56; August 1924, vol. XXX, no 8, 1924, pp. 233-234.

Oliver-Lloyd,Vanessa (photographe) et al., Les croix de chemin au temps du bon Dieu,Outremont, Les éditions du passage, 2007, 224 p.

Simard,Jean, "Témoins d'un passé de foi", "Perspectives", in La Presse, June 17th, 1972, pp. 20-22.

Simard,Jean, et Jocelyne Milot, Les croix de chemin du Québec : inventaire sélectif ettrésor, Québec, Ministère de la Culture et des Communications, 1994, 510 p.

SociétéSaint-Jean-Baptiste de Montréal, Programme souvenir du 24 juin, Montréal,Secrétariat de la Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montréal. Années consultées :1932, 1939, 1950, 1952.

SociétéSaint-Jean-Baptiste de Montréal, La croix du chemin, Montréal, la Société,1923, 156 p.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Albums de croix de ch

emin de E.-Z. M... -

Calvaire

-

Calvaire élevé à l’en

Calvaire élevé à l’en

trée de Saint-E... -

Calvaire normand à Lo

Calvaire normand à Lo

ngueuil (Montér...

-

Char La croix du chem

Char La croix du chem

in et le mois d... -

Croix angle Belle riv

Croix angle Belle riv

ière et route 2... -

Croix aux instruments

de la passion -

Croix de chemin

Croix de chemin

-

Croix érigée près de

Croix érigée près de

la route 138 à ... -

CROIX SOUTENANT UNE N

CROIX SOUTENANT UNE N

ICHE RENFERMANT... -

Croix Vanier à Laval-

Croix Vanier à Laval-

des-Rapides (La... -

La croix de chemin, à

Saint-Joachim

-

La Croix du Mont-Roya

La Croix du Mont-Roya

l lorsqu'elle s... -

Les croix de chemin d

Les croix de chemin d

u Québec :... -

Planches de photograp

Planches de photograp

hies d'E.-Z. Ma... -

Prière du soir à la c

Prière du soir à la c

roix du chemin ...

Documents PDF

-

« La croix de nos chemins »

« La croix de nos chemins »

-

Avant-propos de La croix du chemin (1923), par Édouard-Zotique Massicotte

Avant-propos de La croix du chemin (1923), par Édouard-Zotique Massicotte

-

Extrait de « La petite histoire de la croix du Mont-Royal »

Extrait de « La petite histoire de la croix du Mont-Royal »

![The Croix Fassett [Fassett cross] (Outaouais), © Vanessa Oliver-Lloyd, 2007](/media/thumbs/341/200x0-Croix_de_chemin_coeur.jpg)

![Map taken from Les Croix de Chemin du Québec: Inventaire Sélectif et Trésor [Wayside Crosses in the Province of Quebec: a Selective Inventory of Treasured Heritage Assets], © Jean Simard and Jocelyne Milot](/media/thumbs/427/250x0-ILLUSTRATION_NS_3___nouvelle_version.jpg)

![Wayside cross at Saint-Arsène, MRC [Regional County Municipality] of Saint-Arsène](/media/thumbs/901/180x0-Croix_de_chemin_final.jpg)